2022 Annual Report

I lāhui na‘auao Hawai‘i pono, I lāhui Hawai‘i pono na‘auao.

There will be a culturally enlightened Hawaiian nation,

There will be a Hawaiian nation enlightened.

Activities of the Council 2022

Coordination Activities

“The Education Council shall use funds made available through a grant under subsection (a) to carry out each of the following activities: (1) Providing advice about the coordination of, and serving as a clearinghouse for, the educational and related services and programs available to Native Hawaiians, including the programs assisted under this part.”

Hīpu‘u Native Hawaiian Education Database

Background

In July 2021, The Council awarded American Institutes for Research (AIR) through a competitive bid process a contract to conduct an environmental scan and development of an online clearinghouse. Prior to this, The Council’s research resources have been made available on our organization website. However, our website was not designed to support user interface needs for online searching or to categorize and house varying forms of resources such as multi-media, articles, or streaming video.

The purpose of our online database is a multifaceted approach to meet our statutory mandate, increase data access and Native Hawaiian education research resources with and within our communities, and foster evidence-based policymaking with allied partners at our local, state, and federal levels.

The Council established two parts to address this mandate. The first was to conduct an environmental scan and stakeholder needs assessment that informs the design and delivery of an online database. The second part would be to utilize the stakeholder feedback to shape and inform a user-centered design of the online clearinghouse.

PART I: Environmental Scan, Library Sciences, Database Indexing, and Recommendations

Provide an environmental scan and stakeholder needs assessment that informs the design and delivery of an online clearinghouse of data and information on Native Hawaiian education.

There were four main areas of research identified to harvest data from stakeholders for Part 1 that could inform recommendations for the design and development of the online database that included goals and objectives, types of content, content organization, and user experience (UX). Based on these four areas, four research questions were established:

- What do we want the database to accomplish?

- What audiences should the database serve?

- What content should the database contain and provide access to?

- What kind of user experience should the database strive to deliver?

To obtain the necessary quantitative and qualitative data, we first identified the stakeholder audiences for the database that included primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences. Then we used three research methods to collect data to inform our discovery research: stakeholder interviews, online surveys, and a benchmarking review.

The table below identifies the stakeholder audience and data collection method:

| Stakeholder Audiences | Data Collection |

| Primary Interviewees | |

| Council members, former members, staff, and a current grantee organization. and staff |

Interview, survey |

| NHEP Grantees | Interview, survey |

| Hawai‘i state agencies and Native Hawaiian-serving organizations | Interview, survey |

| Federal policymakers for the state | Interview, survey |

| Secondary Audience | |

| Educational, community-based organizations in Hawai‘i that provide funding or direct services to Native Hawaiians | Survey |

| Native Hawaiian community | Survey |

| Tertiary Audience | |

| U.S. Department of Education staff | Survey |

| Grant funders and philanthropic organizations | Interview, survey |

In addition to the stakeholder interviews and survey responses, a benchmarking review was also incorporated. A benchmarking review is a type of market research that compares organizations, or in this case websites, across existing performance criteria to assess or establish performance standards in an industry, domain, or product class. Having defined standards or levels of performance within that space, organizations can identify improvements or performance targets that fit their strategic plan or their approach to continuous improvement.

Data Analysis

Summarized Findings

The following are summarized findings organized across the four overarching research questions for Part 1.

Hīpu‘u Goals and Objectives

In interviews, the following five themes were cited most often when discussing goals for the Hīpu‘u website development, in the following ranked order:

- Disseminate data about impact/outcomes of approaches

- Disseminate grantee materials that have practical value

- Preference for raw data

- Inform policymakers

- Inform about educational program availability

Types of Content

Potential users of the Hīpu‘u site hope that Hīpu‘u can provide access to data-driven and technical assistance materials, which often are hard to find or require a lot of work to assemble. Those expectations fall into three general categories:

- Data-rich materials to learn about program or policy outcomes, in particular datasets, curated data, or visualized data.

- Technical materials that have practical value (e.g., serving as a reference or presenting best practices).

- Materials that reflect the work and accomplishments of NHEP grantees.

Adding to user preferences for data-driven and technical materials was also stated stated for Hīpu‘u to become a one-stop shop destination for online resources, whereby it would:

- Deliver the convenience of finding everything in one site or being directed to the right location to avoid lengthy and scattered searching;

- Provide access to a wide range of materials, some of which might otherwise require special access;

- Consolidate high-value materials on key topics and in various formats/types to streamline research and learning; and

- Provide access to disaggregated data on Native Hawaiian education in a searchable database.

The content preferences expressed by participants will guide and shape priority criteria for Hīpu‘u in determining which types of content to assemble and make available. These preferences also point to a high level of need and expectations that may be difficult to meet in the short term because some types of materials may take a significant amount of time to collect, curate, and vet.

Therefore, the Part 1 findings suggested to approach the launch and build out of Hīpu‘u in phased releases. The purpose and scope of each release should be carefully framed prior to release to manage user expectations.

- Education programs outcomes and best practices

- Education and well-being research, trends, and metrics

- Socioeconomic issues impacting education policy and programs

- Pedagogical resources and curriculum

With regard to organizing content under a Native Hawaiian well-being section, potential clearinghouse users expressed strong preferences for five subtopics, listed in ranked order:

- Native Hawaiian cultural and spiritual practice and identity

- Mental health and behavioral development

- Healthcare data/outcomes

- Physical health and behavior

- Physical environment and safety

The second layer of organization was proposed by age group, such as the following:

- Early childhood

- Elementary

- Middle school

- High school

- Postsecondary

- Adult education

Zoom polling, surveys, and open-ended interview question responses point to many specific UX attributes and characteristics that potential clearinghouse users prefer and from which we might extrapolate what they would like to see in the clearinghouse. Listed in ranked order, they are as follows:

- A choice of simple search or advanced search

- Filtering

- Related item suggestions

- Metadata-rich result listings

- Quick View

- Feed of the latest resources

In addition, for “next step” options for what users would like to do with a selected item, they ranked the following, of which the first five do not require the user to create an account:

- Download a resource

- See related Items

- Bookmark a resource

- Share a resource

- Print the resource

- Sign up for email updates (requires creating an account)

PART II: Online Clearinghouse Development

The goal of Part 2 is to build on the findings of Part I and develop an online database that will serve as a data repository for Native Hawaiian education that is intuitive and easy to navigate; provides powerful, fast, and flexible search capabilities; meets current needs while also providing a foundation for future growth in scale and scope; allows nontechnical users to manage database content and resources; and is fully secure to withstand external threats (e.g., cyberattacks, viruses). At the completion of Part 1, the summary findings and recommendations established a sound framework for the user-centered design development and project roadmap.

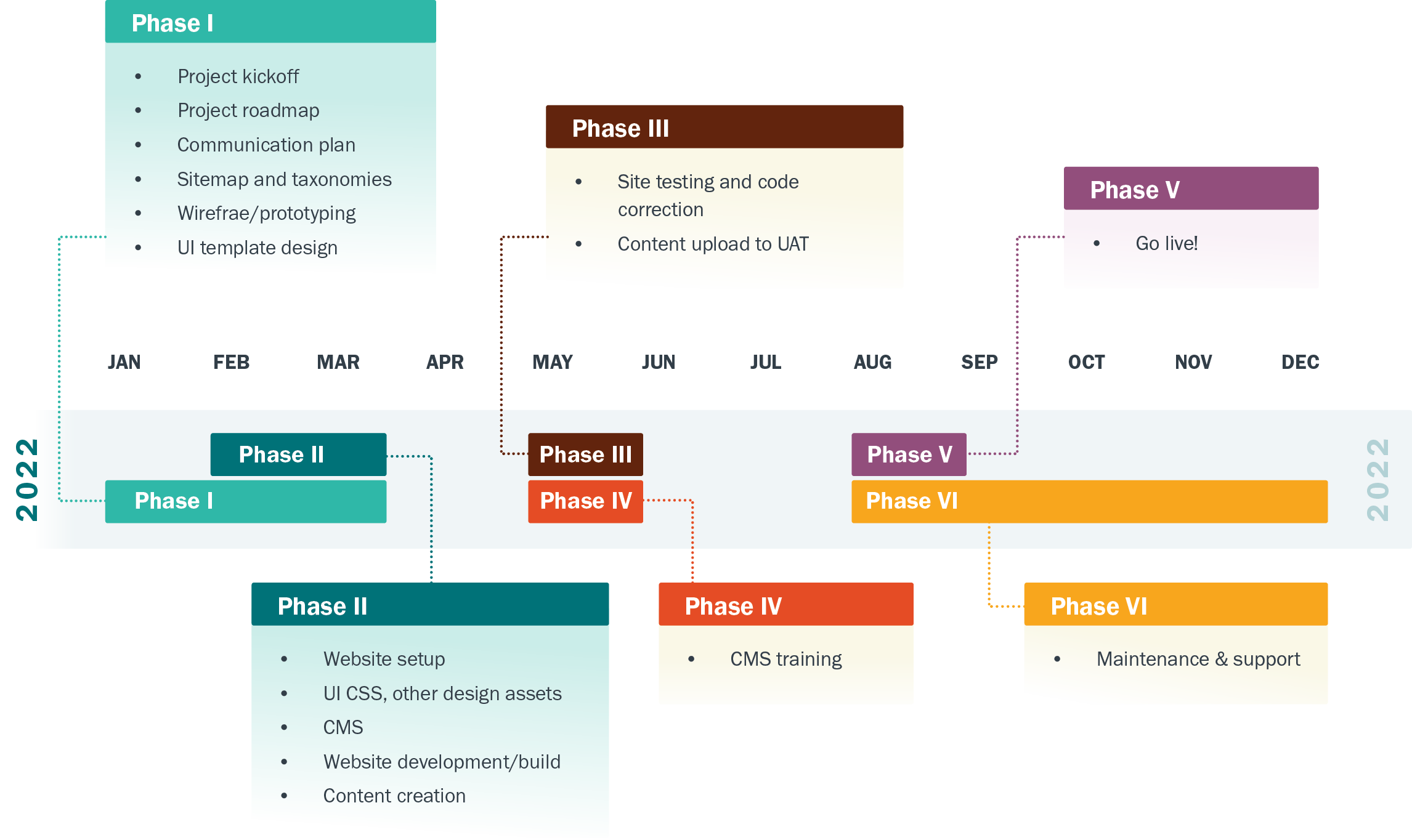

NHEC Part 2 Clearinghouse Project Roadmap

Figure 1. Hīpu‘u Project Roadmap for Part 2: Online Clearinghouse Development begins in February of 2022 through the end of the calendar year for the entire lifecycle of the site development, staff training of the site, and site maintenance and transition.

Part 2: Phase 1 and 2

Phases 1 and 2 of the Hīpu‘u development encompassed significant effort, dialogue, and iterative work in:

Sitemap & Taxonomies: Site infrastructure in how content will be organized and how resources are categorized for search functionality based on key determining factors from Part 1 participant feedback and community-relevant language (i.e. Hawaiian-medium education vs Native Hawaiian language education)

Wireframes & Prototyping: Along with site infrastructure, wireframes were established early on the development phase to visually layout content and functionality of a user journey with simple prototyping for the Council to test features.

Communication: The highly iterative nature of the wireframes and prototyping development meant weekly and biweekly meetings between the Council and development team to create a constant flow of testing, feedback, and updates.

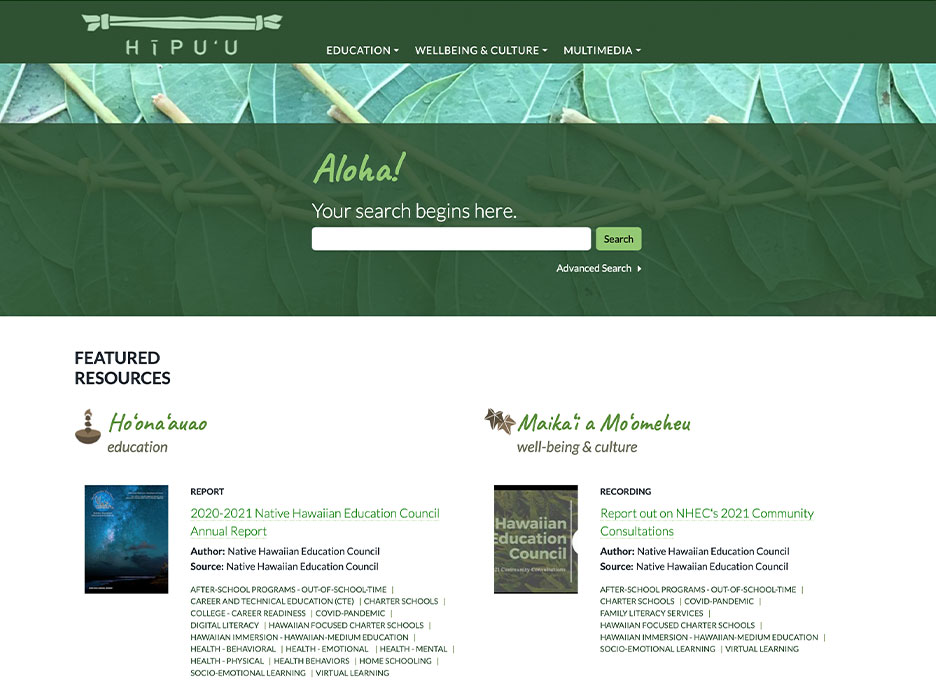

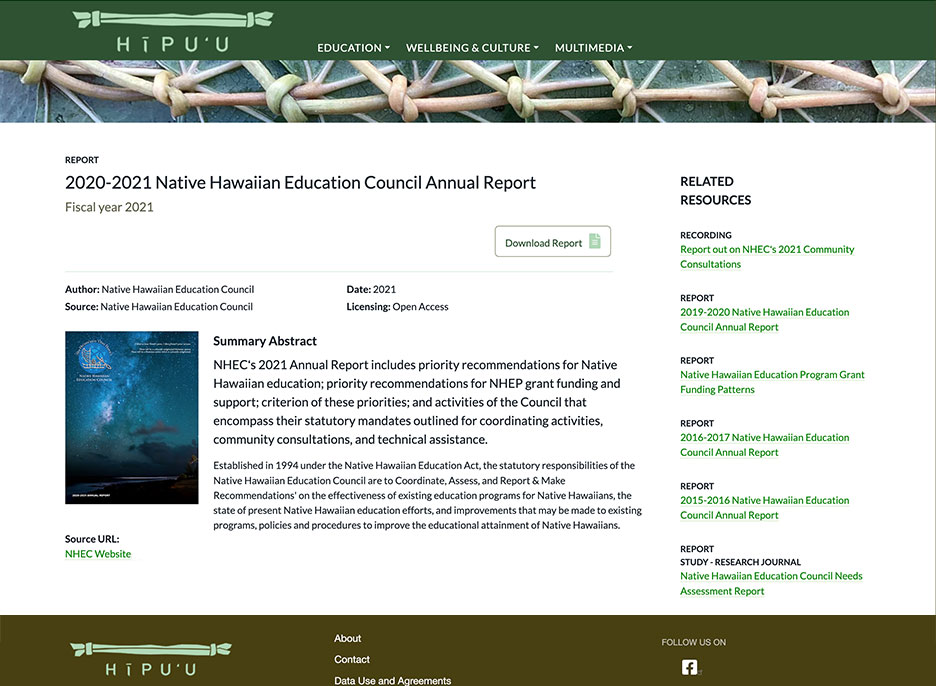

Figure 2. Hīpu‘u home landing page with a simple search field and featured resources within the domains of education and well-being & culture.

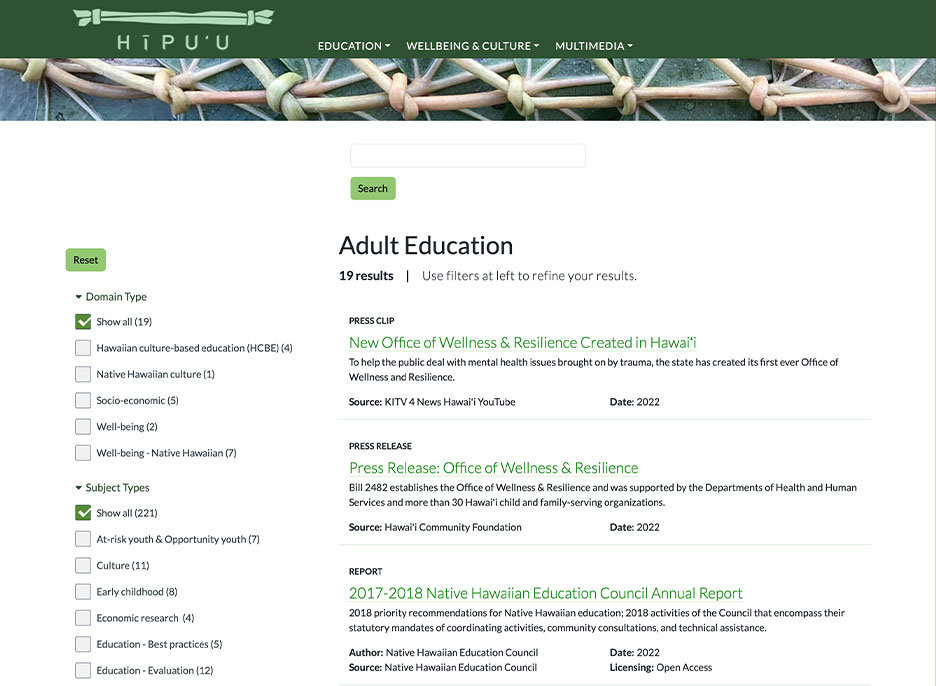

Figure 3. User search interface for Hīpu‘u.org based on domain, subject types, topic types, and further filtered by resource types, target population types, audience types, content types, and multimedia types.

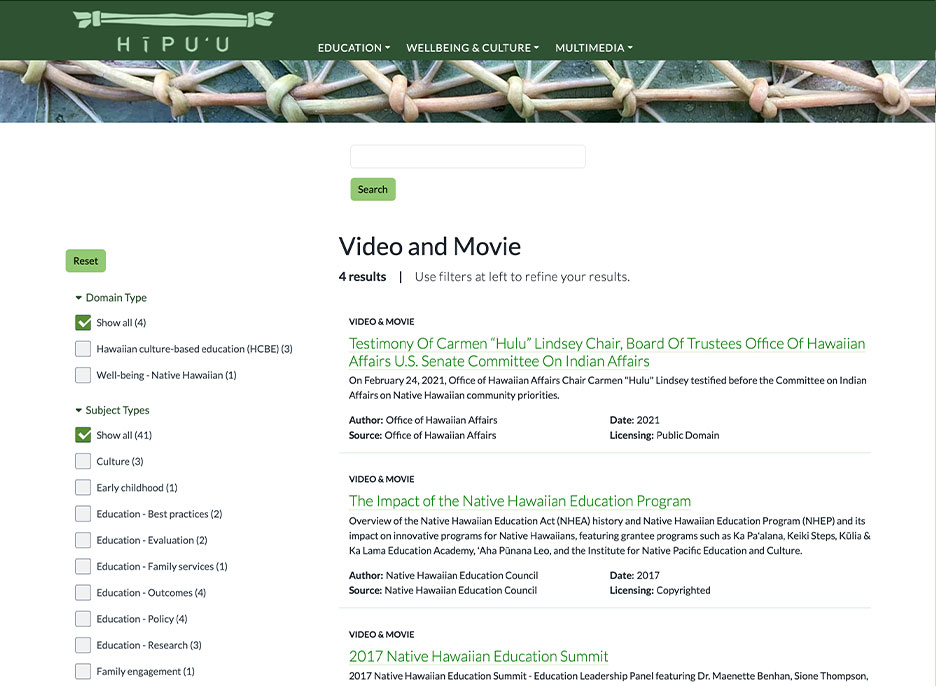

Figure 4. User search interface for Hīpu‘u.org based on multimedia filter that results in resources of videos and movies.

Figure 5. Hīpu‘u resource search result that provides the content type (report), resource abstract, the source URL, download options, and related resources based on the user search criteria.

Technical Assistance

“The Education Council shall use funds made available through a grant under subsection (a) to (1) provide technical assistance to Native Hawaiian organizations that are grantees or potential grantees under this part; (2) obtain from such grantees information and data regarding grants awarded under this part; […] (5) assess and evaluate the individual and aggregate impact achieved by grantees under this part in improving Native Hawaiian educational performance and meeting the goals of this part…”

Impact, Assessment and Learning Study of the 2020 NHEP Grant Awards – Year 1

In 2021, American Institutes for Research (AIR), a national policy analysis and evaluation research firm, was contracted to develop an impact, assessment, and learning study of the NHEP 2020 cohort of grant recipients to effectively measure the progress and impact of meeting the goals of the NHEP as stated in the Act including development of a logic model for the NHEP as a whole.

The purpose of this project is to assess the data collected and produced by the grantees and provide technical assistance on the coordination and collaboration among the NHEP, HIDOE, and grantees to improve access to and sharing of data to inform the administration and evaluation of the NHEP.

Activities for the study are divided into five distinct phases:

- Planning, Communication and Project Management

- Data Collection and Management

- Technical Assistance and Evaluative Analysis

- Impact, Assessment, and Learning Report

- Presentation and Dissemination

The following is a summary of Year 1 project activities and an overview of activities occurring throughout Year 2.

Planning, Communication and Project Management

The study was kicked off in August 2021 with NHEC and AIR meeting to confirm the Council’s vision for the study and ensure a common understanding of its scope and goals, and to discuss plans for data collection and logic model development.

Development of a Program-level Logic Model. AIR worked collaboratively with NHEC executive leadership and the project standing committee to create a draft version of the NHEP logic model. The Council created the vision statement for the logic model and generated early ideas related to long-term outcomes. This program-wide logic model is a living document that AIR continues to develop through grantee engagement activities. To date a small subset of grantees has contributed ideas related to long-term outcomes and potential measures.

Logic model development will continue during the second year of the project (September 2022-August 2023). An all-grantee meeting was held in September 2022, which gathered additional insights from the perspective of grantees and leverages the work they have done on their project level logic models. Community engagement events are being planned for Spring 2023 and will generate insights from the perspectives of some of the communities served by 2020 NHEP grants.

Logic model development will continue during the second year of the project (September 2022-August 2023). An all-grantee meeting was held in September 2022, which gathered additional insights from the perspective of grantees and leverages the work they have done on their project level logic models. Community engagement events are being planned for Spring 2023 and will generate insights from the perspectives of some of the communities served by 2020 NHEP grants.Data Collection Management

Review of Literature and Extant Data

To increase understanding of the Native Hawaiian education context and leverage prior work accomplished by NHEC and other Native Hawaiian organizations, AIR conducted a gray literature review (evidence not published in commercial publications) on recent reports and relevant policy documents. Key topics in the summary of this review include background on the NHEP and the federal Act that created and authorizes the grant program; Native Hawaiian and other culture-based education models; and parent/family engagement frameworks. AIR continue to add to this summary as relevant documents become available and uses this internal document as a reference.

Development of a Program-level Logic Model

To inform the logic model development, data collection, and outcomes data collection tasks, AIR conducted an extant data review to create an inventory of existing data sources that potentially measure relevant outcomes related to student achievement, workforce development, and community health and wellbeing (broadly defined). The extant data inventory was completed in January 2022. AIR continues to refer to the inventory to help locate and describe available outcomes data. The focus in Year 2 will be on finalizing long-term outcomes and identifying measures that align with each outcome. In addition, The AIR team will clarify the short- and mid-term outcomes expected to contribute to those long-term outcomes and specify accompanied measures.

Grantee Engagement

The AIR team developed a grantee engagement plan and began engaging grantees in the logic model development task by asking them to identify long term outcomes and aligned outcome measures. To date, a small group of grant project directors have attended two meetings to design and facilitate an all-grantee meeting that took place in September 2022. Learnings from the September event will support the logic model development and inform the planning of future grantee and community engagement events.

Community Engagement

AIR has engaged two Hawai‘i community-based consultants with experience working in Native Hawaiian communities to plan and facilitate community engagement events that will begin in Spring 2023. This team has developed a community engagement plan and has identified five target communities for initial engagement activities: Waimānalo, Māili, the Ka‘ū -Kea‘au-Pāhoa Complex Area, Keaukaha, and Moloka‘i island. AIR will reach out to NHEP grantees serving these communities and community-based organizations for recruitment. These 2023 events will likely take place virtually, but as the COVID pandemic eases AIR will explore the possibility of conducting in-person events in one or two of the target communities.

Measurement of Outputs and Outcomes

In Year 1, AIR has progressed in this project by collecting annual grantee documents and reports and creating a database to store and code the data gleaned from these reports. To date, all Year 1 documents received from FY20 grantees have been reviewed and data entered into an Excel database. Quality control reviews are in progress and inform ongoing refinements to the database. The AIR team has also begun to collect grantee documents for Year 2 and continue to follow-up on missing documents from Year 1. These documents will be reviewed, and data extracted and entered into the grantee database.

With regard to outcomes data sources, AIR submitted a data request to the HIDOE, as confirmed when meeting with Hawai‘i DXP to discuss data needs for the study. AIR is also looking into options for automated data scraping using R software, which would allow us to retrieve the publicly available data more efficiently in the event that HIDOE does not respond to our request in a timely fashion.

Technical Assistance and Evaluative Analysis

Data Analysis. The AIR team is utilizing Microsoft PowerBI to generate a customizable data dashboard tied to the grantee Excel database. The data visualizations on the dashboard can be displayed in reports and webpages as needed by NHEC. By end of November 2022, A draft PowerBI dashboard will be provided to the Council for review and comment on the most useful data to display visually to inform program monitoring over time.

Development of Data Collection Recommendations. AIR will begin drafting early recommendations related to data collection in 2023. These draft recommendations will be refined in Year 3.

Assistance with Articulating the Outcomes of the NHEP. AIR will begin sharing early learnings from the study with grantees and communities through engagement activities. The details of these activities will be finalized based on learnings from the initial all-grantee meeting (September 2022) and grantee engagement events (Spring 2023). AIR will work with NHEC to identify other relevant venues and forums for disseminating the cohort-level information produced through the study with Native Hawaiian communities across the state.

Impact, Assessment, and Learning Report

Preliminary Reporting and Final Report. AIR will report its preliminary findings to the Council for review and comments by June 2024. The final report is due in July 2024.

Presentation and Dissemination

Council Briefing on Project Status. AIR provided a briefing to the full Council on the Year 1 project activities on August 10, 2022, receiving useful feedback and insights from the members on grantee engagement, community engagement, and data analysis. The Year 2 briefing is scheduled for July 2023.

NHEP Grantee Coaching and Consulting Sessions

In FY22, NHEC continued its partnership with researcher and evaluator Linda Toms Barker to provide one on one coaching and consultation to all current NHEP grant projects on a range of topics: program logic model support, performance measurements systems, evaluation design and criteria development, professional development strategies, evaluation use and program planning, program data collection and more.

This year, a total of 37 consultations with 24 grant projects. Seventeen of the sessions occurred from November 2021 through January 2022 as grantees were revising and finalizing their project logic models. The other 20 sessions occurred from April through July 2022 as grantees were preparing annual performance reports (APR).

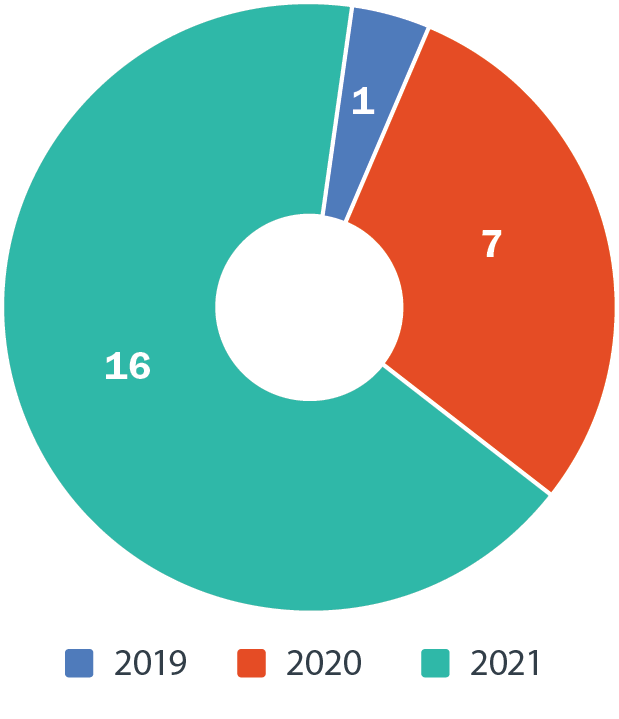

Grantee Cohorts

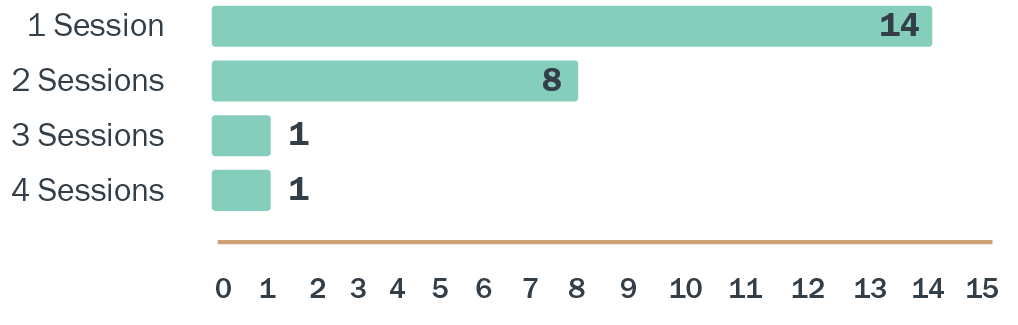

Number of Grantees by Number of Sessions (N=24)

Of the 24 grant projects that participated in the session, one is from the 2019 award cohort, seven from the 2020 cohort, and the majority (16) from the 2021 cohort. Most participating grantees requested only one coaching/consulting session, but ten had multiple sessions as shown in the chart.

Focused on four major topics:

- Logic model design/development issues (raised by all of the grantees coached in January 2022, and all but five of the grantees coached in the spring/summer)

- Performance measures (raised by all but four of the grantees)

- Clarification of instructions for completing annual performance reports (APRs) (raised by all but two of the grantees coached in the spring/summer)

- Program evaluation issues (raised by six of the grantees)

Consultations included reviewing grantees’ applications and logic models in advance of the consulting sessions, phone discussions with project managers and/or evaluators, reviewing and providing feedback on grantee draft materials, and in some cases providing example documents.

Logic Model Development

Concerns raised:

- How to identify targets and measures, given that not all approved logic models distinguished short/medium/long term outcomes.

- Confusion about whether performance measures should focus on outputs or outcomes.

- How to use the logic model to structure data collection and reporting.

Recommendation and other supports:

- Recommended simplifying overly complex logic model to make it more useful.

- Explained relationship between objectives, logic models and APRs.

- Assisted in distinguishing short-term, medium term and long-term outcomes.

- Encouraged grantees to include performance measures for critical outputs other than targets for numbers served (which are reported in a difference section of the new APR) as well as for short/medium term outcomes.

Identification of Performance Measures

Concerns raised:

How to prioritize rather than have 20 or more

performance measures. How to ensure that performance measures are meaningful to project managers. How to use logic models to identify performance measures.

Recommendations and other supports:

Assistance in identifying performance measures. Recommended revisions to ensure project objectives, intended outputs and outcomes, and performance measures align.

Annual Performance Reports

Concerns raised:

What is the correct way to respond to some of the

instructions for the APR? In particular, what is the correct way to report financial data and outcomes, given that the time frame for the APR is less than

the full grant year? (These concerns were mostly voiced by 2021 grantees. Some 2020 grantees were concerned about how the APR requirements were changing.)

Recommendations and other supports:

Used PPT slides from ED that were used with the nine pilot grantees to describe the new MAX Survey report. Clarified APR instructions. Emphasized importance of including other evaluation results in the narrative, since the APR template only specifically requires numbers served and numerical results for performance measures.

Program Evaluation

Concerns raised:

How to find a qualified evaluator (using standard UH system did not yield qualified candidates) Evaluation requirements unclear – ED does not seem to prioritize evaluation, evaluation reports are not required, unclear whether/to what extent to invest in program evaluation. Large, somewhat overwhelming number of performance measures requiring different data collection efforts. How can survey instruments be improved? How to analyze and report the data.

Recommendations and other supports:

Recommended posting evaluator positions with Hawai‘i Pacific Evaluation Association and commercial job posting sites rather than limiting to the University of Hawai‘i recruitment system. Recommended prioritizing data collection to focus on data most useful to the Project managers to minimize data collection burden and ensure data analysis focuses on most useful information. Recommended following through with evaluation plans developed during grant writing and early program implementation stages, even if not explicitly required by ED. Reminded grantees that while ED prioritizes numerical data, it is the qualitative data that provides insights into how to improve the numbers. Recommended evaluating why participants drop out by collecting data from non-completers. Recommended labeling scales (e.g., strongly agree, etc.) rather than just using the numbers. Provided suggestions for how to analyze and report pre-post data, addressing percentage targets vs numerical targets, how to report on annual vs 3-year targets, and other analysis and reporting issues specific to individual projects.

Community Consultations

“The Education Council shall use funds made available through the grant under subsection (a) to hold not less than 1 community consultation each year on each of the islands of Hawaii, Maui, Molokai, Lanai, Oahu, and Kauai, at which […] (2) the Education Council shall gather community input regarding […] (B) priorities and needs of Native Hawaiians; and (C) other Native Hawaiian education issues; and (3) the Education Council shall report to the community on the outcomes of the activities supported by grants awarded under this part.”

FY22 Community Consultations

For fiscal year 2022, ‘A‘ali‘i Alliance LLC (A‘A) was contracted to plan, convene, and facilitate regional community members that may also include students, student families, and community employers connected to Native Hawaiian education and workforce in Hawai‘i; monitor and report to the Council of consultation activities; and evaluate the results of the community consultation activities and responses gathered to inform future priority funding in relation to:

- Public awareness and engagement with current NHEP-funded programs and services;

- Gathering community reflections on immediate and emerging educational intervention, bright spots or promising practices, as well as needs and challenges;

- Understanding student, ‘ohana (family), and workforce demands for educational resources and programming; and

- Improving the consultation process and data with community guidance and insights to trends as they relate to specific educational trends in the distinct geographical regions of Hawai‘i.

Using these goals, the consultant and NHEC staff designed a consultation process that included the following components:

- A succinct and easy to understand set of guiding questions;

- A flexible schedule to include both virtual consultations and in-person consultations;

- Trained and prepared facilitators and Council members inspire positive engagement during consultations; and

- Both island-specific consultations and affinity group consultations to attract a more diverse set of stakeholders in Native Hawaiian education.

2022 Community Consultation Schedule

January 20 – K-12 and Higher Ed

January 22 – Student, Teachers, Parents

January 27 – Out of School and ‘Āina

February 3 – Early Childhood

February 19 – Windward Community College (in person)

March 3 – Waimānalo, O‘ahu

March 10 – Hilo, Hawai‘i

March 10 – Waimea, Hawai‘i

March 12 – Central Maui

March 14 – Lāna‘i

March 15 – Moloka‘i

March 30 – open to anyone

March 31 – Hawai‘i

April 5 – Moloka‘i

April 8 – Maui

April 9 – Wai‘anae, O‘ahu (in person)

April 13 – Anahola, Kaua‘i (in person)

April 14 – Līhu‘e, Kaua‘i (in person)

April 14 –Kekaha, Kaua‘i (in person)

April 21 – Lāna‘i

April 23 – Ko‘olauloa, O‘ahu

April 26 – open to anyone

The 2021 consultations focused on mo‘olelo (story) of strength and bright spots in Native Hawaiian education during the pandemic. In 2022, the focus shifted slightly to build upon mo‘olelo of strength and ask which programs, components, people, or services are absolutely essential to Native Hawaiian education. An appreciative inquiry approach was employed in 2022 to seek positive and uplifting stories to draw out creative problem solving and critical analysis. Participants were asked to share their mo‘olelo about the essential programs and services they would like to see prioritized.

The guiding questions for the consultations were:

- Based on what we learned during COVID-19, what education programs proved to be essential? What characteristics of programs or specific programs can you not live without?

- How did the community meet essential needs?

- What gaps in Native Hawaiian education remain? Why do these gaps persist?

The first question sought specific references to programs and services. The second question asked how community deployed these essential programs during such challenging circumstances, and the final question asked participants to think about what gaps remain in Native Hawaiian education—particularly if these gaps prevent essential programs and services from flourishing—and why the gaps persist if they are essential.

A total of 22 consultations were scheduled from January through April 2022. A total of 17 virtual consultations were planned and facilitators were able to host five consultations in-person after COVID-19 safety restrictions were lifted across the state. Originally, the schedule included 13 in-person consultations, but due to the Omicron surge, many of these consultations were moved to virtual meetings for safety or under recommendation by community members that participation would be better online. Given the uncertainty of the pandemic and recommendations that community members preferred virtual meetings in some cases, 17 consultations stayed in the virtual meeting format for 2022.

In regards to the “educational role” of participants ( i.e., current student, teacher at any type of school, at any level of education pre-K through post-high, etc), a full 45% of participants identified as current students, 42% identified as current teachers, and 13 participants or 19% identified as both a teacher and student.

This year, more challenges related to attendance at consultation. Participants noted feeling more fatigue with online meetings, wariness toward the safety of in-person meetings, community frustration with tourism that made some in-person meetings contentious, and a struggle to balance rapidly opening in-person activities—like youth sports—with meetings. The pandemic made clear there is no perfect option: each participant comes with preference for either in-person or online engagement and a busy schedule. Given this, the mo‘olelo reflected in this report only represent those who were able to juggle schedules successfully and make time to attend. This has important implications in that busy individuals may be missing from the conversation.

Responses to each question were captured and coded. Several themes were prominent across the three questions and are interconnected.

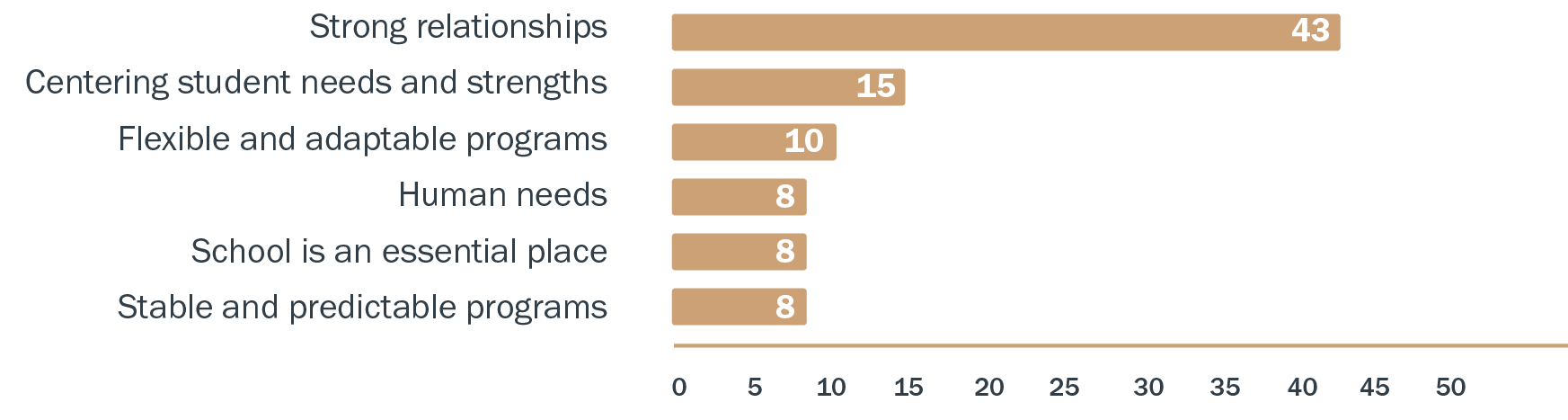

Responses to question 1: Based on what we learned during COVID-19, what education programs proved to be essential? What characteristics of programs or specific programs can you not live without?

Strong relationships (connections, strong ties across educational stakeholders) were the most mentioned essential characteristic Native Hawaiian education. Other essential characteristics included stu-dent-centered education, flexible and adaptable programs, programs caring for human needs, school itself as an essential place, and stable and predictable programs. Participants talked about how important it is for students to have strong connections with their schools, teachers, administrators, counselors, mental health professionals, peers, and a strong connection to culture in order to be successful. Participants also talked about the essential connections between families and schools and other community resources.

Participants also said that putting student needs, strengths, talents, and interests at the center of the educational experience is essential. Not only do participants believe children need to be approached as individuals in the learning environment, but also as people who are unique and sometimes have difficult home environments.

Participants also mentioned that flexible and adaptable programs are essential. Flexible programs are those quickly able to change to meet emerging needs, especially pandemic-related issues.

Interestingly, the next most essential program characteristic after flexibility was a notion that programs or schools that provided a sense of stability, predictability, and structure proved essential. Participants did not mean to say that programs that refused to change did well, but rather, those who adapted while also providing a sense of stability—like predictable scheduling even if the program time of day changed—were most helpful.

It is also important to emphasize that schools themselves are essential. School helps to organize society: it is a predictable place where students go and where the services provided therein are relatively helpful and positive. Schools are essential places because of the human needs to which they attend. Taken together, these two categories of essential pieces of Native Hawaiian education show that both the physical space of schools is essential as well as the services provided at school.

Responses to question 2: How did the community meet essential needs?

Facilitators tried to get participants to focus on the essential programs they had just mentioned in the first question and on how the need for essential services were met. Gaps were filled by community coming together and getting things done, making things work with available resources, by building connections, and having preference for smaller organizations and their capabilities.

Community also tried to get creative with the resources available to make essential programs possible. Some participants said they used the resources of their communities, and others were able to find success accessing institutional resources. What is clear is that communities have more tools and resources than maybe gets acknowledged.

Participants also mentioned that filling the essential needs in Native Hawaiian education was accomplished through relationship building. This comes as no surprise given the important role relationships play in Native Hawaiian education in general and as shown in the previous question.

The responses show that community was able to meet the essential needs of Native Hawaiian education by taking ownership to problem solve, work together, practice resourcefulness, and keep the scale of the work manageable. These are all critical approaches to successful community work, so it comes as no surprise that these elements are mentioned most. Programs looking to be successful in the future would do well employing similar approaches.

Responses to question 3: What gaps in Native Hawaiian education remain? Why do these gaps persist?

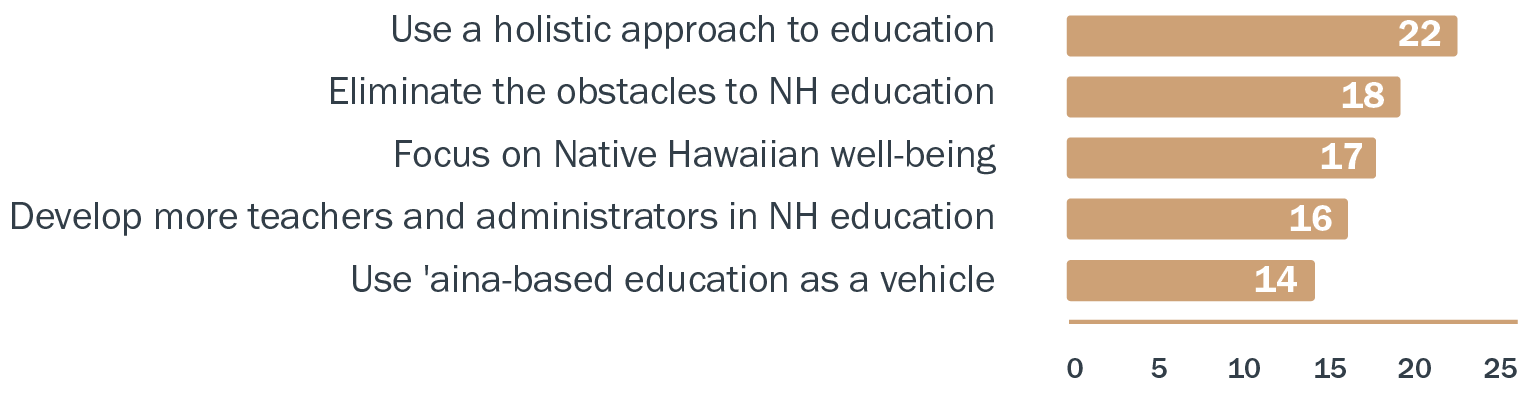

The final question was an attempt to direct participants with concerns about Native Hawaiian education toward sharing what they believe to be the root cause of any gaps or problems. Not all participants were able to think through the gaps in Native Hawaiian education and why the gaps persist during the time allotted; others came with professional experiences in education to share why gaps persist. Once participants were able to voice root causes, facilitators were able to probe for solutions to these root causes. It was found that potential points of leverage that the Native Hawaiian education system can use to solve some of its most challenging and persistent gaps. The most common idea is to create a more holistic education system, followed by eliminating obstacles to Native Hawaiian education, and focusing on Native Hawaiian well-being.

Participants talked most about the failures of the current educational system—both Native Hawaiian education and otherwise—as siloed, piecemeal, and unable to understand the holistic wellbeing of learners. Participants said that if education were constructed in ways that address total wellbeing, used processes that supported student success, and had an organizational culture that preferenced learning, Native Hawaiian children and all children could be more successful.

In addition to the larger, foundational pieces of education needing to operate as a healthier system, there are also many barriers on the micro level to wellbeing. It is important to note that one online meeting consisted of participants from the Native Hawaiian hearing impaired and deaf community. These individuals expressed intersectional issues as people with disabilities and as Native Hawaiians. In addition to this specific issue from the deaf community, others expressed general concerns not being able to access Native Hawaiian education, not knowing about programs, their challenges with special needs in general, and the lack of willingness among school administrators to address barriers to learning.

Many participants brought up the conflicts between Western and indigenous wellbeing as the reason why gaps in education persist. Also, many brought up the lack of mental, emotional, or spiritual health resources as the reason why student achievement remains low. More approaches to holistic well-being could help address some of the persistent gaps in Native Hawaiian education, but this will not be easy work.

Across many consultations, participants wanted to raise a red flag that there is a critical shortage in teachers, particularly Hawaiian immersion and Hawaiian medium education teachers. Facilitators heard anecdotes about the number of open teaching positions at schools, students staying in the cafeteria most of the day for study hall due to a lack of teachers and substitutes, and the lack of fully credentialed teachers. Additional follow up from NHEC and other important statewide advocates is needed to confirm the true level of teacher shortages and also improve the flow of certified teachers to the classroom.

‘Āina (land, place) continues to be an important vehicle not just for better educational outcomes, but potentially greases the wheel that could bring resolution to other challenges in Native Hawaiian education. For example, ‘āina is a vehicle for building student understanding of connection and relationships was an essential component of Native Hawaiian education in Question 1 mana‘o. It also is a vehicle for spirituality, mana, and social emotional learning that does not have to be loaded with religious connotation as was talked about in the paragraphs above. There are also barriers to ‘āina-based education that prevent ‘āina from becoming the solution to many Native Hawaiian educational issues.

Responses to the third question of the consultation process shows the numerous challenges in Native Hawaiian education as well as the tremendous amount of work that could be done to make more progress. Using a holistic approach that creates a more comprehensive educational process, eliminating all the micro-level obstacles, focusing on what Native Hawaiian well-being means, making sure there are enough qualified teachers who can also ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i (speak the Hawaiian language), and using ‘āina-based education as a vehicle to champion Native Hawaiian education causes is extensive work. The next sections will reflect on the overall mana‘o from the consultation process in an attempt to find practical and manageable steps to realizing the vision of NHEC.

Conclusion

When using a wide perspective, Native Hawaiians have much to be proud of in terms of the achievements and progress in Native Hawaiian education. Native Hawaiian education has expanded, innovated, and elevated cultural values, practices, and language for decades. The participants in the 2022 consultations shared that now is not the time to be complacent–there is much work to do for current learners and future generations. The hope is for the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on Native Hawaiians to be an unusual and small instance in a much longer history of a growing movement. In order for the pandemic to leave no scar, participants suggest the work lies in recreating a system of services that take care of the whole learner, and many participants continue to put their effort and dreams in reaching this goal.